On November 16, 2010, the Thai police arrested Viktor Bout, the “Merchant of Death” on an Interpol red notice. A notorious international arms trafficker, Bout emerged as one of the pre-eminent dealers in the early 1990s. Officially indicted on charges that Bout sold 5000 AK-47s, 700 to 800 surface-to-air missiles, and other weapons to undercover U.S. DEA agents posing as FARC rebels, Bout has a lengthy history of involvement with rogue entities. He has conducted business deals with the likes of Charles Taylor in Liberia, Jean-Pierre Bemba in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Paul Kagame in Rwanda. In cultivating relationships with these authoritarian leaders, Bout’s weapons have remained a persistent factor in terrorism, crime, ethnic cleansing, and local and regional destabilization.

On November 16, 2010, the Thai police arrested Viktor Bout, the “Merchant of Death” on an Interpol red notice. A notorious international arms trafficker, Bout emerged as one of the pre-eminent dealers in the early 1990s. Officially indicted on charges that Bout sold 5000 AK-47s, 700 to 800 surface-to-air missiles, and other weapons to undercover U.S. DEA agents posing as FARC rebels, Bout has a lengthy history of involvement with rogue entities. He has conducted business deals with the likes of Charles Taylor in Liberia, Jean-Pierre Bemba in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Paul Kagame in Rwanda. In cultivating relationships with these authoritarian leaders, Bout’s weapons have remained a persistent factor in terrorism, crime, ethnic cleansing, and local and regional destabilization.

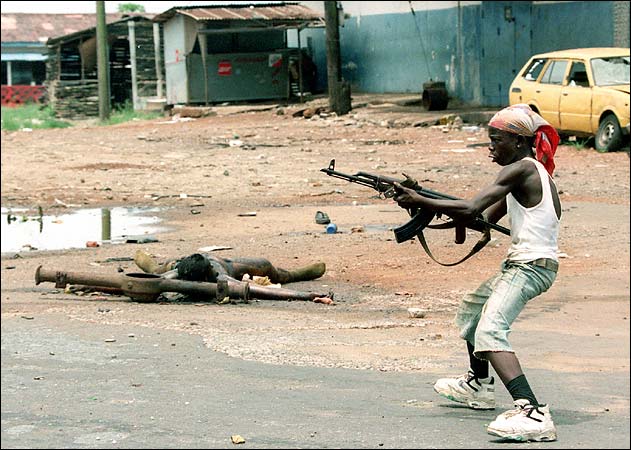

In fact, numerous studies of military small arms have documented their role in perpetuating instability and death. The United Nations convened a conference in 2001 where they noted that small arms were the principal weapons in 46 of the 49 major conflicts in the 1990s, in which 4 million people died. Furthermore, in 2004, Human Rights Watch identified 18 nations where child soldiers are still used—and the overwhelming weapon of choice for these under-aged soldiers is the AK-47, due to its ease of operability. Although the trade of other weapon platforms has declined in the past couple of decades, the sale of small arms has remained persistent. Estimates of the annual legal trade of these arms range between $7 billion and $10 billion. The “illegal” trafficking of small arms is valued around $2 billion to $3 billion a year.

AK-47s are popular weapons in numerous internal conflicts for several reasons. Because they are manufactured in more than 40 countries, these rifles are relatively easy to obtain and can be extremely cheap to purchase. In Angola, it is possible to buy an AK-47 for as little as $15. And as many of these conflicts involve poor militant factions, the cheap price of these small arms makes them attractive. Furthermore, because the gun has few moving parts, it hardly ever jams—giving it an advantage over more sophisticated rifles such as the American M16. It works well in different types of weather: the rain, extreme heat, and the cold. While its accuracy is not always reliable, its ability to fire 600 rounds a minute gives it potency during combat. In one startling anecdote, American soldiers in Vietnam reported that they found AK-47s “buried in rice paddies for six months or more that were filthy and rusted shut” but that still fired perfectly after they “kick[ed] the action bolt with the heel of a boot”. Finally, the weapon’s low weight and durability set it apart in the small arms market.

This proliferation of AK-47s has empowered militias and paramilitary groups to wield power equivalent to or even greater than that of a national military force. For example, in 1989, Charles Taylor and roughly a hundred of his troops stormed the presidential palace and overthrew the government. Then, utilizing the AK-47 as a form of political currency, Taylor promised weapons to anyone who worked to keep him in power. The ability of one soldier to rapidly fire bullets indiscriminately has struck fear in many regions of the world. The AK-47 has been typically utilized not as a tool for liberation but as a tool for hindering freedom movements. It has been the rifle of choice for states to repress any opposition. East German border guards shot unarmed civilians fleeing for West Germany with AK-47s. In uprisings in Prague, in Alma-Ata, in Baku, and in Riga, the AK-47 saw use in silencing freedom. Chinese military soldiers utilized these small arms at Tiananmen ,and Uzbekistan soldiers fired them in the Andijan Massacre of 2005. Innocent Kurds were shot by Iraqi Army soldiers using these weapons. The genocide of Srebrenica also capitalized on the killing efficiency of the AK-47 to kill innocent Bosnian men and boys. While most observers fixated on the threat of nuclear weapons during the Cold War, little attention was given to the proliferation of small arms. However, in the aftermath of the collapse of many Communist states, entrepreneurial minded individuals seized on the opportunity to loot weapons caches or arsenals. This chaotic period allowed for the easy transfer of weapons across the Eastern European bloc all largely hidden from the eyes of the international community. What the international community failed to realize was the impact that these potent weapons would actually hold. Even to this day, arms-control specialists look to the price of AK-47s in a nation’s arms market to determine the degree of destabilization in a land.

Sources include:

1. Chivers, C.J. "The Gun". Simon & Schuster. October 2010.

2. Patrick Herron, Nicolas Marsh, Matt Schroeder, and Jasna Lazarevic. "Small Arms Survey 2010".