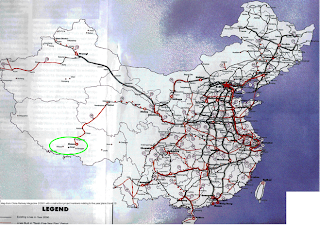

According to this map published by the European Commission in 2010, much of the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China is as “inaccessible” as Greenland, and is less accessible than most of Siberia. Time required to travel to the nearest city over 50,000 inhabitants, is, for much of Tibet, between two and ten days.

Tibet’s geographic isolation from much of the rest of China—due to its rugged topography and high altitude on the Tibetan Plateau—has contributed to its cultural and ethnic differences from the rest of China. Though Tibet has been part of China since 1951, the Tibetan Autonomous Region is still over 90% Tibetan, while the Han population, dominant in eastern China, stands at around 6%. Tibet’s average population density is roughly two people per square kilometer—making it the country’s least dense region.

Despite Tibet’s geographic isolation, the region has been a source of tension for China’s Communist Party, as Tibetans have historically resisted Chinese rule. Struggles between Chinese and Tibetans have persisted, generating ethnic riots in 2008. Since then, however, the Chinese government has decided to focus on business and infrastructure to try to integrate Tibet with the rest of China; in 2009 alone, the Chinese government invested $3 million dollars in the Tibetan Autonomous Region.

These infrastructural investments may change both Tibet’s accessibility and its ethnic unity. On September 26, 2010, the Chinese government began construction on a railroad extension that will connect Shigatse, Tibet’s second largest city, to Lhasa and hence to the rest of China. A trip from Shigatse to Shanghai will take roughly forty-eight hours, though construction on the extension is expected to take four years and cost the equivalent of two billion U.S. dollars.

Shigatse, the administrative center of Xigâze Prefecture, is only about 450 kilometers (280 miles) from the Nepalese border. Extending the railroad from Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, southwest to Shigatse will not only allow for better connections between eastern China and south-central Tibet, but it will also facilitate a further extension to the border of Nepal, perhaps eventually to Kathmandu.

Though the Chinese government lauds the railroad project in Tibet for its potential to promote cultural unity, many Tibetans feel differently. Shigatse is the location of the Tashilhunpo Monastery of the Panchen Lama, Tibetan Buddhism’s second highest monk. As such, the city has become an important symbol of the power struggle between the heads of Tibetan Buddhism and the Communist Party of China; in 1995, the Chinese government took the then six year old Panchen Lama into “protective custody,” and Tibetans have heard little news of the Panchen Lama since then. Many Tibetans took this as a Chinese effort to gain control over the Dalai Lama and undermine Tibetan autonomy, and thus are hesitant to see further Han influence in the region. Increasing the accessibility of Shigatse via the national railway will allow the immigration of large number of Han Chinese, potentially weakening the cultural integrity of the city.

In addition to the railway extension, a new airport will soon be completed in Shigatse. The Peace Airport, as it will be named (a name that mirrors “Friendship Highway”—the portion of the Chinese highway that runs between the Tibetan cities of Lhasa to Zhangmu), will be Tibet’s fifth civil air transportation facility. Although the airport was set to be complete by October 2010, construction has apparently been delayed and the latest reports expect that it will open in November at the earliest.

The concern for Tibetans is not the gaining of access to the rest of China, but rather the potential for large-scale Han migration further into Tibet. Though many Tibetans resent the influx of Han Chinese, transportation development has generated strong economic growth. In 2009, the Tibetan economy grew by 12 percent, an even higher figure than that of China as a whole. Still, it remains unclear how much of this economic growth benefits native Tibetans, rather than Han investors and immigrants.

The railway extension will also affect mining. Tibet is thought to have China’s largest deposits of copper and chromium, minerals that are in high demand in eastern China’s burgeoning industrial cities. A strong railroad network will make transportation of workers and minerals more financially and logistically feasible.

The planned extension of the Tibetan railway is highly controversial. Will it dramatically dilute the Tibetan population, stimulate friendship between China and its Tibetan Autonomous Region, or intensify Tibetan sentiments for independence? Only time will tell.